Why that "OK" table on natural immunity is not "okay"

A table circulating social media demonstrating the "inferiority" of natural immunity to vaccination, raises many more questions than it resolves.

(DISCLAIMER: The following article represents solely my opinions and interpretations of data, for the purposes of public discussion and debate. It does not represent medical advice, nor does it represent the views of any organization I am affiliated with. Please seek the advice of your own physician.)

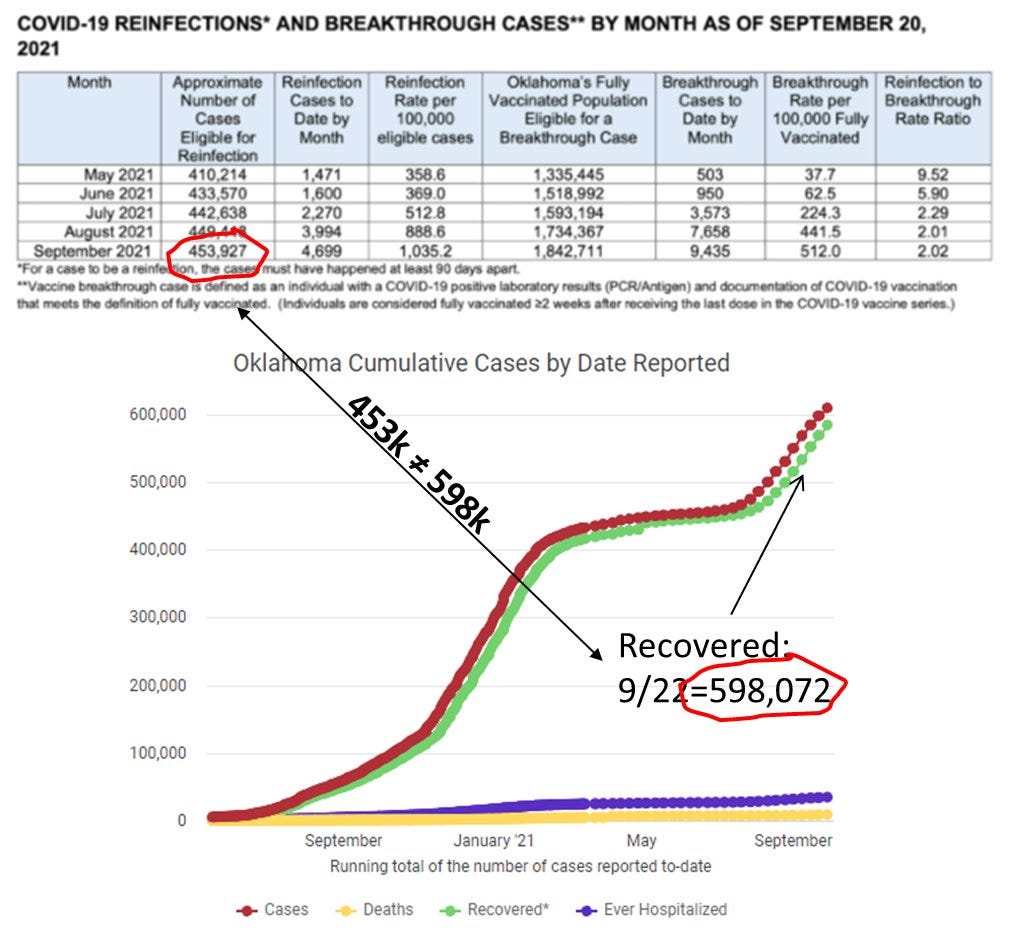

It seems that every time there is a rising narrative that counters the prevailing wisdom of public “experts”, a state-level department of health releases data or a study to counter the challenge. This was the case with the now famous “KY” study, attempting to show the benefit of vaccination in the previously infected. Now, there is another dubious table, from the Oklahoma DOH, making the social media rounds, attempting to show that rates of reinfection (in the naturally immune) are significantly greater than breakthrough infections (in the vaccinated). It is unclear where exactly this table comes from (and the exact methodology used), but it was disseminated in this news article. The main table making the retweets is this, as annotated by one prominent Twitter influencer, Eric Feigl-Ding:

In this table they claim that there is rise of reinfection (~3x) in previously (presumably unvaccinated) persons, and from May to September, this is 2-9x as much as breakthrough infections in fully vaccinated people. Is this the “smoking gun” that finally dismisses natural immunity? As always, the devil is in the details, so let us take a deeper dive.

First, lets take the table at face value — that the rates of infection are accurate (we will investigate this assumption later). This data shows another stunning (but neglected) trend, that the rate of breakthrough infections are rising astronomically comparatively to that of natural immunity.

So, based on this, breakthrough infections in the vaccinated increased nearly 14x, compared to only nearly 3x in the naturally immune, during the Delta period of the pandemic. Why would this be? There are several possible reasons. First, other studies (like this NEJM study) have shown a waning effectiveness of the mRNA vaccines (particularly Pfizer), starting around June (when this bump begins) — hence, the “booster” discussion. Second, this distinct difference in infection rate growth may be related to naturally immunity having some advantage in protection over vaccinated immunity, particularly with Delta. This in fact would be consistent with Israeli Gazit study, and the Indian Satwik study, which were set during the Delta phases of the pandemic. Nevertheless, with such a difference in the rate of growth between reinfection and breakthrough, its hard to conclude that vaccination is dramatically outperforming natural immunity.

But, cheerleaders of this OK data table also point out that the absolute incidence rate of reinfection is 2-9x greater than the rate of breakthrough infection in the vaccinated. They claim that this fact alone, should compel mandatory vaccination in the previously immune. To assess this claim, however, we need to understand the underlying methodologies in order to determine that this is a fair comparison. As far as I could search, I could not find any detailed description of the methodology, other than the footnotes provided with the table. So, let us focus on one aspect of this comparison — the so called “approximate” number of cases eligible for reinfection (2nd column) and the fully vaccinated population eligible for breakthrough.

In the above figure, the bottom graph is taken from the OK Department of Health’s COVID dashboard, with the green line counting “recovered” individuals. The numbers for May, June and July generally track with what is reported in the table (~450,000 recovered). However, in August and September, the number of recovered go up rapidly. And by September 20th, there are nearly 600,000 recovered persons in OK. Why does the OK table not correlate with this rise? This is because the authors of this table do not consider a person “eligible” for reinfection until 90 days after first infection (due to persistent positive phenomena), but, only wait 14 days after vaccination to be eligible for breakthrough. This has the effect of “frontloading” the denominator for the freshly vaccinated group (and least likely to have a breakthrough), while “backloading” it for the recently recovered — and certainly introducing bias into the data and its topline conclusions. In effect, the newly vaccinated breakthrough rate is 2.5 months delayed from the newly recovered group — and we see this in the table where breakthrough rates in August are similar (and even exceed) reinfection rates in May. Based on this alone, you cannot compare, on an absolute basis, the rates of reinfection with the rates of breakthrough.

And then, there is this methodological curiosity introduced by tabulating the data monthly. In the vaccinated group, lets say a person gets their first jab on May 1, and their 2nd jab on May 15th, becoming eligible for breakthrough on May 28th. This person would only be at risk for 3 days in May— but would be counted in the “fully vaccinated” denominator for the entire month. This effectively dilutes the denominator by the newly vaccinated. The same would occur for a newly recovered individual (with a 3 month delay, depending on when they got their infection), but because the rate of vaccination growth is exceeding the rate of recovered growth (~50% vs. 10% over 5 months), this effect of dilution is more exaggerated in the vaccinated group. Rates of infection are usually measured in events per person-time, however, this OK table does not correct for days “at risk”.

Who is included in this “approximately eligible” population? Since the May-August numbers closely track the total recovered, it is unlikely they are excluding recovered individuals who have gotten vaccinated (~20-40% of recovered), or including those who may be serologically positive (but without history of a positive test, e.g. asymptomatics). The CDC itself estimates that only 1 in 4.2 cases were reported — so the “approximate” denominator could be much larger by several factors, and the reinfection rate much lower. (This would not only change the denominator population, but how infections/ reinfections/ breakthrough infections are classified as well). Serological status is relevant, as it could serve as an important litmus test on immunity. Many argue that immunological status, rather than vaccination or previous infection history, should be the “gold standard” for designating protection.

There is also the known issue that vaccinated individuals are less likely to get tested, even if symptomatic, even compared to those who are recovered. In the early months of May, June, July — when we were lulled into vaccination overconfidence, it is very likely that many asymptomatic (or weakly symptomatic) breakthrough infections simply were not recorded due to lower propensities to get tested. But as Delta became more pervasive, testing rates in the vaccinated (and recovered) may have increased. This could explain the large 9x ratio early, that reduces later to 2x. But, this is yet another reason you simply cannot fairly compare the reinfection and breakthrough rates, on an absolute basis.

Additionally, the average recovered individual has had a longer period of natural immunity (as early as March 2020), compared to those vaccinated (starting December 2020). To make a true comparison, one needs to account for the total time since their protective exposure. This methodological correction was actually done by the Israeli Gazit et al. study, which showed that the 6-fold advantage in protection from natural infection, improved to 13-fold, when the previously infected and vaccinated, were time-matched for their exposure event. So to be a true comparison, the authors of the table should have only taken the newly recovered, to be matched with the newly vaccinated — and follow the reinfection/breakthrough rates. Of course, this is not what was done.

The point of the last five paragraphs is that there are many confounding factors that play into the accuracy of these reinfection and breakthrough rates. And comparing the two on absolute terms, though each is derived from different sources with differing confounders, is simply fallacious. It’s like using the absolute scores from the Lions-Bears and Packers-Vikings games, in order to predict who would win a hypothetical Lions-Vikings game. Notwithstanding that my Detroit Lions will generally find a way to lose, a comparison of absolute scores in different competitions would be flawed.

So, what can we glean from this data? There are some studies out there that support the notion that vaccinated immunity is greater than natural immunity. The recent Pfizer clinical trial update, suggests this the case (albeit with very small numbers). Another “real-life” Moderna study outside of the Kaiser Permanente system suggests the same. However, both of these studies reported a tragically low vaccine efficacy in recovered individuals (18-33%), and a the recent Moderna trial update decided to not even report a vaccine efficacy for recovered persons. On the flip side, several studies have shown that natural immunity exceeds vaccinated immunity: Gazit et al., Goldberg et al., Shrestha et al., Satwik et al., and the J&J randomized control trial. In this group, both the Gazit and Shrestha trials were during the Delta phase of the pandemic. With the current state of the data, it is difficult to conclude that either natural or vaccinated immunity is superior to the other. It is reasonable to conclude, however, that they are practically equivalent and individually dependent on circumstances (brand of vaccine, serological status, time elapsed from infection/vaccination, occupational hazards, etc.). I present a systematic review and analysis on this issue, in a pre-print here (currently in peer-review).

This is not to say recovered persons should avoid vaccination entirely, and vaccination may in fact prove valuable in a subset of recovered individuals. However, each recovered person should be evaluated individually on their risk/benefit profile, with the guidance of their physician. An older and retired recovered individual exposed in March 2020 likely has a much different risk then a teenager who contracted COVID this summer, but the former may face no mandate whatsoever, yet the latter may be facing a stringent university or employer mandate ignorant of natural immunity. As such, the “one-size-fits-all” approach is inefficient. For the recovered, clinical equipoise should be used. And, at the very least, our public health officials should provide basic guidelines on the decision-making for vaccination in recovered individuals, rather than ignoring it entirely.

There is a final point to be made here — and that is context of this table set against the greater situation situation in Oklahoma which is avoided in the Twitter narrative. During this same May-Sept 20th period, there were approximately a total of 149,526 COVID cases in the state. According to the above table 14,034 were in eligible recovered persons, while 22,119 were in the fully vaccinated. The remaining 113,000 far exceeds either the fully vaccinated breakthroughs or recovered reinfections. Clearly, the unvaccinated and non-immune person should be the real focus of public health officials, rather than displaying irrational contempt for the recovered.

The use of half-baked, cherry-picked data is not “OK”, and only serves as twitter fodder for those media influencers who seem dogmatically aligned to a policy, rather than the objective clinical reality. If our public health leaders begin to acknowledge the relevance and nuance of natural immunity, they can send a powerful message to all hesitators that science, not authority, is truly in our guiding light.